WELCOME TO THE BURGH BLOG

The Maryhill Burgh Halls blog offers a rich tapestry of stories, research, and reflections that celebrate the history, heritage, and community spirit of Maryhill, Glasgow. It features contributions from local historians, volunteers, and staff.

Scroll down to read and email info@mbht.org.uk if you would like to share something of your own.

Lest we forget

Words by John Thomson

The plaque in its original location, on the walls of St George’s Episcopal Church. (Credits: Max McConville)

Earlier this year, on Friday, 25th April, at the appropriate time of 11 am, a bronze, memorial plaque commemorating 78 Maryhill men who died during World War I, was unveiled, here, at Maryhill Burgh Halls.

The ceremony to mark its return was attended by local community members, serving and veteran military personnel, and representatives from the 6th Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. It was a full and proper ceremony with a colour party, the laying of wreaths and an address from Paul Sweeney, MSP.

The plaque which was made in 1920 at a cost of £100, had originally been hung at St George’s Episcopal Church in Sandbank Street and dedicated in April 1921, but in subsequent years, it seemed to have disappeared. It was eventually found in the storeroom of the Royal Highland Fusiliers Museum in Glasgow, following extensive research by Adie Meehan, who came across it while tracing family history – Adie having family connections with Percy Lawrence McLachlan, his wife’s great uncle, one of the men listed on the plaque – but the men are also listed elsewhere. To mark the occasion, a commemorative booklet was produced, featuring short biographies of many of the fallen.

But that doesn’t have to be the end of it.

We, at the Halls continue to seek additional information, photographs, and stories from family members and descendants. Please contact heritage@mbht.org.uk to share.

But the ceremony reminded some of those attending of another, missing, memorial and the story of some other lost men of Maryhill – the 211 men of the now demolished Lyon Street in Maryhill who emerged from a half dozen closes in that street and went on to enlist in almost every Scottish regiment that fought in the First World War.

A Roll of Honour was created for them as well. It gave the bare details of the men who had enlisted, including sixteen names of men who never came back, twenty-seven who were wounded and two who were ‘simply’ marked missing on the roll.

This roll, apparently, hung in a local pub - the Garscube Bar - until it was demolished in 1962, as was Lyon Street, and the roll vanished.

Various attempts to locate it were made, including a project involving Oakgrove and St Joseph’s RC primary schools, but its whereabouts remain a mystery and any information regarding its location would be much appreciated.

The plaque at the rededication ceremony.

The plaque we do know about, remembering the 78 men, is on permanent display in the Halls on the mezzanine floor on a wooden plinth which was created by Boomerang Woodworking CIC. The names represent real people – sons, fathers, brothers and neighbours – who lived in and around Maryhill, before heading off to war, never to return.

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

- The fourth verse of ‘For the Fallen’ by Robert Laurence Binyon (1914)

Artist highlight: Hilda Goldwag

Words by Alyssa Mills

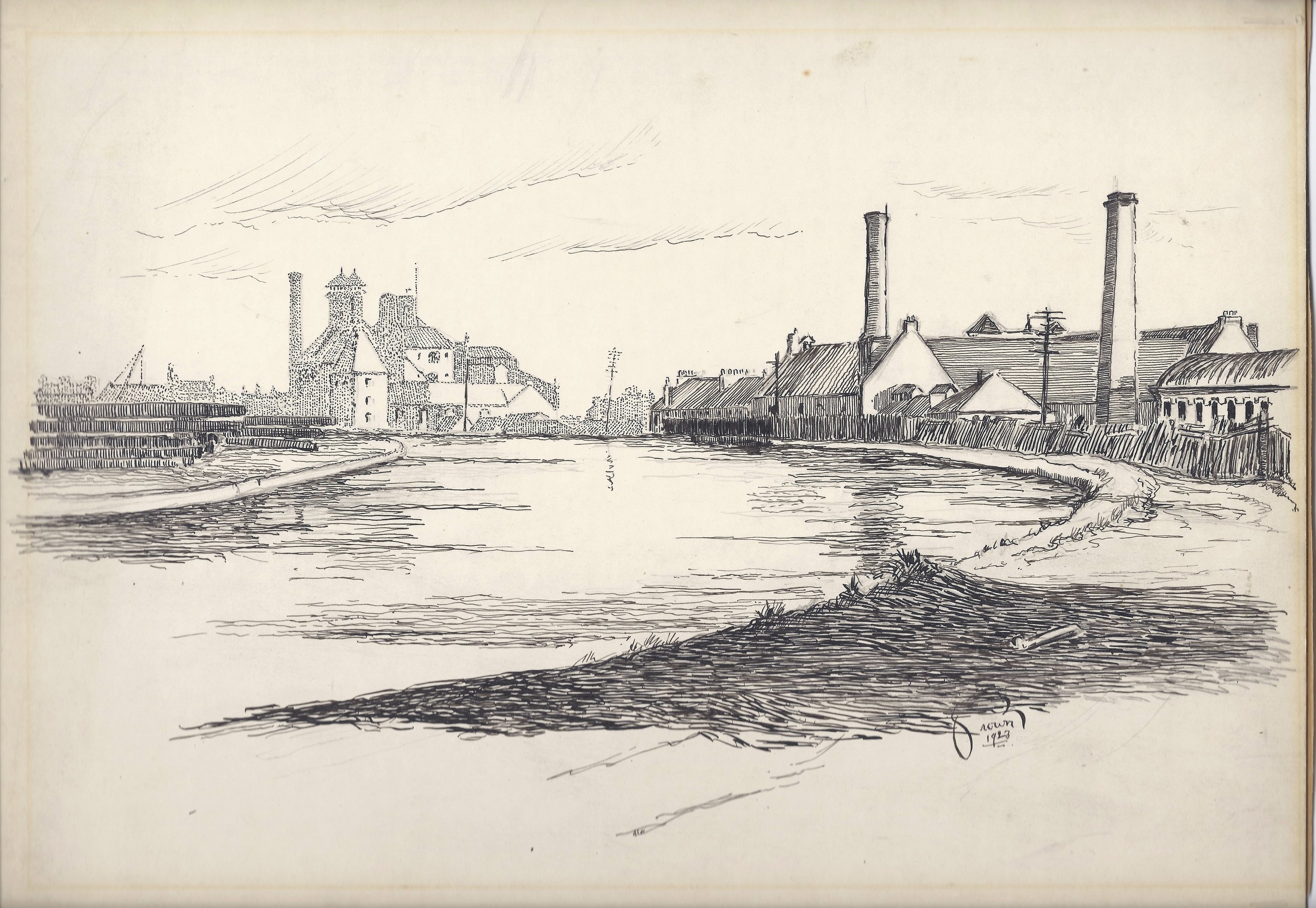

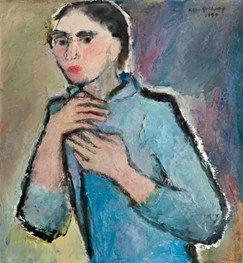

October (1962) via East Dumbartonshire Council

In a time of renewed focus on questions of culture and identity in Britain and Scotland, it is vital to recognise the outstanding contributions of immigrant and refugee artists, such as Hilda Goldwag. Looking at Goldwag’s charming, lived-in tenements or idyllic landscapes on the banks of the Clyde, it is clear with every brushstroke the love Goldwag had for her adoptive city. Goldwag takes a different approach to her contemporaries, neither highlighting the poverty and social unrest which accompanied Glasgow’s industrial decline nor neglecting its reality in favour of a glamourised portrait of the city.

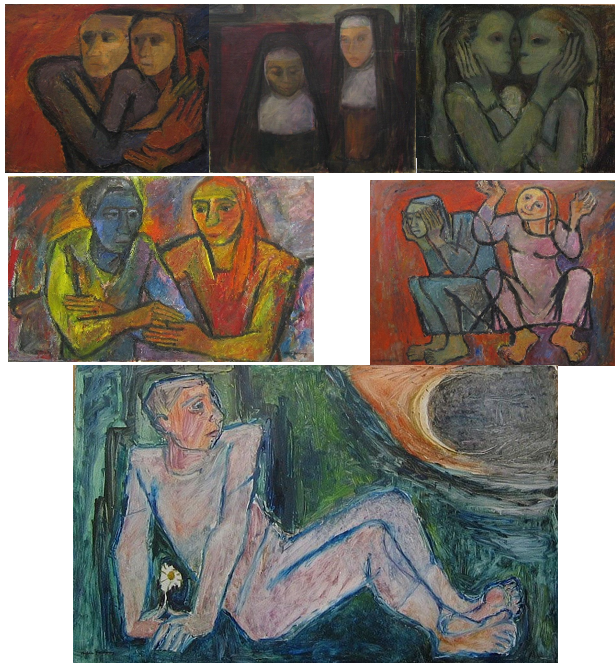

Conversation via Clare Henry Art Journal

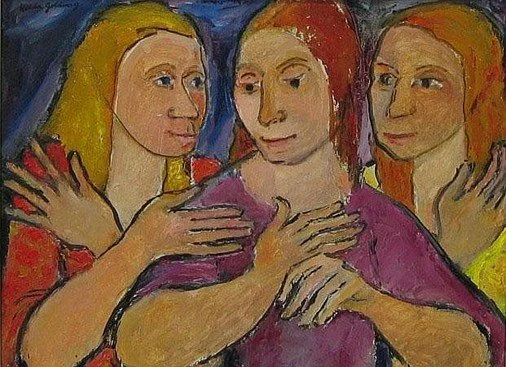

Having trained in painting as a young girl in Vienna, Goldwag was influenced by the less traditional compositions and colours being forwarded by European expressionists, especially the German-led Die Brücke style. While an increasingly abstract style was gaining prominence in British art, Norbert Lynton (1994) describes Die Brücke as uniquely bright in colour and ‘assertively primitive’ in form, with ‘at first sight no sign in their work of direct social comment or even of personal anxieties.’ Both Goldwag’s figures and landscapes feel nostalgic and honest - a realistic depiction of the world through the lens of someone who cares deeply about their subject. But to say Goldwag’s art is apolitical is inaccurate. Her comforting, domestic scenes are defiant in their affection, creating a theme through over 60 years of painting. Her work is intimate and optimistic, a lens through which the oft-dilapidated canals and streets of Glasgow are transformed into a vibrant cityscape which feels instantly familiar to those who love Glasgow like Hilda.

Early Life

Blinds via McTear’s

Hilda Goldwag was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1912, and trained as an artist against the backdrop of the growing Nazi regime. Only a year after graduating with a degree in graphic arts, Hilda had to leave her home and family for the safety of the UK, moving to Edinburgh and shortly later, Glasgow as a refugee. Her family, expected to follow six months later, were approved to travel the day WWII broke out, leaving them stranded in Austria. Goldwag’s mother, brother, sister, brother-in-law, and young nephew were eventually killed. This grief is recurrent in Goldwag’s work, as is the sudden isolation she experienced as the sole surviving member of her family, alone in an entirely new and unfamiliar country. Her painting Blinds evokes the unnerving mixture of fear and curiosity she must have been feeling in her early years living in the UK.

Despite not pursuing her art full-time until retirement, Goldwag quickly moved from domestic help for a Church of Scotland minister to Head of Design for a Glasgow printworks, primarily designing scarves for Marks and Spencer's and working as a freelance illustrator for children's books, cards, and magazine. She also enrolled in life drawing classes at the Glasgow School of Art in 1945. Perhaps her most widely distributed work is the original illustrations for Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses (1955) for Harper Collins.

Making A Life

Cecile Schwarzchild (left) and Hilda Goldwag (right) in the 1940s

via Scottish Jewish Archives Centre

Cecile Schwarzschild (1915–1998) via Scottish Jewish Archives Centre

Mirror Image via McTear’s

Shortly after Hilda’s initial move to the UK, she met fellow refugee Cacilie Zoe Schwartzchild, or Cecile, in a Quaker meeting house in Edinburgh. The two became quick and enduring friends, and did war work alongside each other at McGlashan Engineering Works in Glasgow. The two remained close for decades until Cecile’s death in 1998. Even before she began painting full-time, Hilda painted her lifelong companion many times from life and from memory. The portrait above was painted shortly after Cecile’s death, depicting her young, as Hilda may have met her. Even where Cecile isn’t explicitly the subject of Goldwag’s art, the relationship between these two women lingers in her many figure paintings of couples - young and old; familial, platonic, and romantic - who appear to comfort each through a terrifying and uncertain post-war world. Both women were torn away from beloved family by the Holocaust and lived in a world defined by grief. The importance of this companionship to Goldwag’s life and work cannot be overstated. Hilda’s work in the years after Cecile’s death speak to an enduring loneliness which is echoed in the myriad forms of grief experienced by its audience

Depicting Glasgow

Artist Assessing Her Work 18-07-90 by David Holgate

While Hilda worked primarily in creative and design work post-war, she continued painting as a passion, usually using oil paints and a palette knife on board, as canvas was prohibitively expensive. From the 1950s until her death in 2008, Hilda would pile her supplies into a shopping cart and cross the city and especially Maryhill on city buses, leaving her completed paintings to dry on the luggage racks. She completed dozens of paintings in this period utilizing her distinct and evocative expressionist style to represent Glasgow’s crumbling tenements criss-crossed by washing lines, the declining industrial technology overtaken by the city’s great green places on the banks of the canal, and, with the same brush, the weary but determined people of Glasgow. While avoiding explicit or heavy-handed political imagery, Goldwag nonetheless leverages dynamic posing and framing, bold colours, and complex shape language to bring to life the everyday dichotomy a city that was post-war and post-industrial, and yet on the verge of a cultural revival. These domestic scenes are honest and familiar, such as Springtime Courting Scene, which is immediately familiar to the thousands of Glaswegians who visit its many parks every day for a picnic or to soak up brief rays of sunlight between rainstorms.

Springtime Courting Scene

via Glasgow Life

If one thing is clear to the viewer of Goldwag’s paintings, it's a deep and enduring love for her adoptive city. Her landscapes are broad in subject, depicting the Forth and Clyde Canal and the tenements and factories on its banks, flowers, farms, waterfalls, rivers, and more. In regard to Goldwag’s landscapes, artist Alexander Moffat claims 'her intimate glimpses of canal sides, snow covered streets, trees in blossom, suggest an optimistic view of urban life'.

Broken Fence via McTear’s

As a Glasgow transplant myself, the lens through which Hilda Goldwag depicts her home is intimately relatable. Her imagery is honest, never over-glorifying and neither highlighting the symptoms of industrial decline and poverty which is and was ever-present in the city. The crooked churches and winding canals are the heart of a city built by and for its workers, many of whom are, like Hilda, refugees and immigrants. Even where figures are absent from the painting, her landscapes are lived in. One example is Broken Fence, which depicts a fence twisted and rent by a violent storm. The composition and colour are dynamic, and the lighting is low enough to disorient the viewer before the image comes into focus. The painting is chaotic and disorienting, giving the viewer the feeling of being outside during a heavy storm, wind whipping about. These works are whimsical and heartfelt without leaning towards the absurd; and represents a very conflicted time for Glasgow’s identity with nuance and hope.

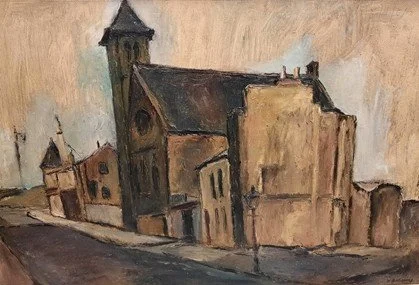

Church on Maitland Street via East Dunbartonshire Council

Dam Overspill on display in Maryhill Burgh Halls

With protests against immigrants and refugees taking place across the UK, it is more essential than ever to recognize that there are few who love and contribute to the UK more than its immigrants and refugees. The idea of ‘protecting British culture’, often invoked in debates about immigration and identity, too often overlooks the invaluable contributions of the many immigrant-led communities and subcultures that have shaped the nations. Artists, engineers, politicians, craftspeople, writers, and labourers across the country have contributed to the complex tapestry of the culture we live in. Hilda Goldwag gave up everything for a chance to build a life free from oppression, including, unfortunately, her family. Hilda Goldwag is one of few Glaswegian artists whose work primarily depicts the city itself, and more than that, Hilda herself is a part of the fabric of the city. By painting in situ, and in so many locations throughout the city, Goldwag’s process was as much art as her finished work, and her and her shopping cart loaded with paintings and supplies became a familiar sight to Glasgow’s residents. Looking through a collection of Goldwag’s paintings serves as sort of tour of the city, preserving a tumultuous period of its history in work that speaks to both to its reality and its underlying spirit.

In her lifetime, Hilda Goldwag received modest recognition but was never considered a renowned artist. She exhibited her work in Gourock, Greenock and at the Lillie Art Gallery in Milngavie; received awards from the Glasgow Society of Women Artists; and was a professional and exhibiting member of the Scottish Society of Women Artists, the Paisley Art Club and the Milngavie Art Club. It is impossible to question Hilda’s talent, but one must wonder her intention when creating art. Her style, which so tenderly depicts friends and strangers alongside tenements and canal scenes, each viewed through an eye which finds beauty because of, and not in spite of, its flaws, speaks to an artist who has found comfort and community amid impossible circumstances. In times like these, when the world seems to be falling apart, there is a quiet resilience in seeking out the beauty of our local space and working to make it better. Hilda Goldwag, and countless refugees and immigrants like her, have made essential contributions to the towns and cities they call home, and it is vital that their current and future place in Scottish culture is fiercely protected.

You can see Dam Overspill here in Maryhill Burgh Halls.

Explore some of the rest of Hilda’s work below, with paintings chosen to emphasise the breadth of style and subject which Hilda lent her considerable skill and unique perspective to bring to life. All paintings featured here are found at Invaluable Auctions site.

In order, paintings are as follows. Portrait Study of a Woman, Old Woman, Schoolgirl on the Beam, Shadow, Nightmare, Man Helping Man, Old Man with Daughter, Icy Crags, Ripple, Woman in Shades of Blue, Dance, Two Faces, Two Nuns, Twin Heads, Women, Contemplating the Moon, and The Guide.

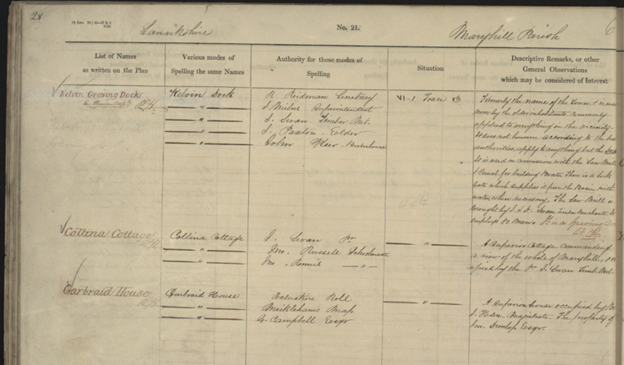

Maryhill – a look back to looking ahead

Words by John Thomson

Kelvindock in December 1967 by David Holgate (Drumchapel Camera Club)

In 1978, a young American lady from Missouri, according to the Evening Times, was given ‘the task of rebuilding Maryhill’ which was a journalist’s way of explaining that Marilyn Higgins was a Glasgow District Council Planning Officer charged with implementing the Maryhill Local Plan, the biggest of its kind in Scotland.

Marilyn went on to say that ‘Maryhill and Missouri may be different, but Maryhill has so much character and personality I think it's going to be quite something.’

Aye. Right.

Mind you, it’s not the first time that Maryhill’s future, and indeed, its past, have been discussed in the press and it would be interesting to know what some of those writers would think of Maryhill today. A random trawl through the newspapers of fairly recent times can reveal a lot.

In 1968 C(harles) A. Mckean, who went on to become a prominent architectural historian, described Maryhill as a village where ‘the beautiful and romantic Kelvin is overgrown with weeds and surrounded by rubbish………The canal is concealed behind walks and hoardings, and the view over to the hills is obscured by dingy street lights and disfigured by waste and derelict ground.’

The answer was simple.

‘The canal (should) be put to good use and its banks cleared of the corrugated iron shacks, walls and hoardings. The canal is there to be seen, not to be hidden, for it has the most beautiful situation.’

His concern was that the canal was to be destroyed, given up to yet another motorway scheme trampling its way through the Glasgow streets.

The Glasgow journalist and bon vivant, Jack House, was another one to extol the virtues of the canal but particularly where the aqueduct carries the canal over the River Kelvin, described by some (in Maryhill) as the Eighth Wonder of the World and by others as

‘the beautiful and romantic situation of the aqueduct carrying a great artificial river over a deep valley 400ft in length, where square-rigged vessels are sometimes seen navigating at the height of 70ft above the heads of spectators, affords such a striking industry as pleases every spectator and gives it a pre-eminence over everything of a similar nature in the kingdom.’

And do you know what? Their dreams came true.

The revitalised Kelvin Walkway links Glasgow city centre with Milngavie and from there to the West Highland Way.

The canal was cleared and re-emerged as more than just a much used waterway between the East and West coasts of Scotland. There’s an art park on the ‘other side’ of the canal featuring Bella the Beithir, a 120-metre-long momentous sculpture situated next to the new Stockingfield Bridge, commissioned by Scottish Canals and a major source of interest to locals and visitors alike.

Further down the canal, on the way into town and the reinvigorated Speirs Wharf, is Hamiltonhill Claypits Local Nature Reserve, the biggest inner-city parkland in Glasgow with a superb view over the whole of Glasgow and an amazing range of wildlife from deer to bumble bees – not bad for a disused quarry and old and decrepit wasteland which is now a thriving community reserve.

But there’s more so much more in these press cuttings than the green, green grass of Maryhill.

In 1986, as highlighted in the Evening Times, the locals of Maryhill took on the might of the, then, Scottish Office and Strathclyde Regional Council in order to save a wall – but this was no ordinary wall. This was the wall surrounding the Wyndford housing estate in Maryhill – formerly a huge army barracks where Rudolf Hess, a deputy of Adolf Hitler, was briefly detained during World War II in his unsuccessful bid for peace. The Community Council saw it as an ‘important piece of local history that ought to be preserved.’ And not only did they save the wall, but they also saved the barracks’ guard house and the bollards offering protection from the Maryhill Road. There are some photos of the wall on the mezzanine floor of Maryhill Burgh Halls.

Ah, yes, the Halls.

Built in 1878, and designed by the distinguished architect, Duncan McNaughton, they had been allowed to fall into wrack and ruin but in 1981, the Evening Times described the fight of Maryhill Burgh Community Centre Trust (sic) to buy the Halls for £100 in order to rebuild them.

They were successful but, according to the Times, they still had to find £500,000 to combat dry rot and pay for the much needed restoration. That was to be in the future and there were many hills to climb before the actual Halls re-building and refurbishment by the current Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust was to begin.

This wasn’t until 2009 and by then, it had become a £9.2 million restoration project but a very successful one. It offers office accommodation for rental, as well as recording studios and a private nursery. It also provides excellent exhibition space for a whole range of exhibitions and currently has a major tenant in the Maryhill Hub, which, in itself, provides a wide range of activities for the area, following its need to move from the redeveloped Wyndford housing scheme.

So much of this story, about the Kelvin and the Canal and the buildings in the area, are available from the Halls in the guise of a range of well written and well illustrated walking guides to the area available from the Halls’ Reception.

But, yes, built in 1878, so that must mean that in 2028, the Halls will celebrate their 150th Anniversary. So, what does the future hold for the building?

The Evening Times got it right all those years ago.

‘It is a fine old building. As a community centre it would give the new Maryhill a heart. All power and support to the people who have taken on such a tough but worthwhile task.’

What do you imagine Maryhill’s future to be?

We would like to thank Richard Ward for generously sharing newspaper clippings that supported our research.

The Smuggler’s Stone: Whisky, Violence, and Justice in 19th-Century Maryhill

Words by William B. Black

Sketch of the canal between the Old Basin and Firhill Basin, 1920 - Maryhill Burgh Halls Collection

In his memoir of Maryhill, Random Notes & Rambling Recollections, Alexander Thomson mentions the

‘Smuggler’s Stone.’ Apparently it stood on the canal side of Maryhill Road, almost opposite Braeside Street, but was lost to view when the canal company erected a fence around 1870. As no trace remains today it must have been removed around the same time.

At the beginning of the 19th century, whisky smuggling was an expanding business in the West of Scotland, partly due to the high rate of duty imposed on the lowland districts. The produce of illicit stills along the margins of the highlands found a ready market in the Glasgow area and the toll road from Drymen, which ran through Maryhill was a route used frequently by the smugglers. Among those was a gang known to be operating from Aberfoyle, including in its number Duncan McFarlane, the carrier from Gartmore. At the beginning of April 1813, James Anderson, a customs supervisor, had intercepted eight of them at Canniesburn Toll, all of whom were seen to have tin containers strapped to their backs. It was known that this was the normal mode of transport and that each container could carry five gallons of spirit, around twenty-three litres. Unfortunately the gang was on the return journey to Aberfoyle and the containers were empty, preventing the excise officers from taking action. However, as the smugglers passed, they showed that they were armed with stout cudgels (a short, thick stick used as a weapon) and made serious threats at the excise men. That this was no idle threat had been shown on 16th March after excise officers captured whisky near Bishopbriggs. As they returned to their base at Port Dundas they were attacked by four armed men, who recovered the whisky. In this attack, one of the customs officers, Quintin Dick, had been stabbed three times.

During the month, intelligence was received that the Aberfoyle gang were to make another run and plans were made to ambush them. After dark, on Thursday 29th April, eight excise officers left Port Dundas, including Dick, who had recovered from his wounds sufficiently to be on duty. All of this party was armed, at least two carrying stuff sticks, stout wooden sticks within which was concealed a removable spike with a sharpened tip. Officially, they were used to probe suspicious parcels but would provide a useful defence against armed smugglers. In addition, three of the party carried pistols, although the usual customs weapon, the cutlass (a short sabre), was not provided, although this was usual when armed resistance was expected.

It was known that many in the local population were sympathetic to the smugglers, so to avoid detection they came along the canal towpath until they had passed Firhill Bridge. As the canal continued towards Ruchill Bridge it came within 30 ft (9 metres) of the Toll Rd (Maryhill Road), where it was about 10.5 ft (3.5 m) lower than the towpath. On the opposite side of the road, the ground rose steeply on a hill known as Sheepmount to a height of 41 ft (12.5 m) above the road, with no other obvious escape route. Today this ambush point is above Braeside Street, where the road curves towards Kelvinside Avenue. In 1813, there were no houses on this stretch, the closest being the lodge for Kelvinside Estate, which stood at the top of what became Kelvinside Avenue, while on the opposite side of the road was Kelvinside Cottage.

Ambush site - from NB 1859 OS Map, most houses shown did not exist in 1813

The ambush party was on site just after Midnight, concealing themselves on the Sheepmount side of the road and, after an hour and twenty minutes, they heard a party of people coming from the Maryhill direction.

The night was very dark and the smuggling party spread out, probably as a precaution against all being caught by an ambush. As the first group passed, the excise officers jumped out onto the road and ordered them to drop their burdens but, in the excitement, failed to identify themselves as excise officers. However, later, most of the smugglers, of whom there were eight, admitted that they did not doubt the identity of their assailants. In the initial attack, the unfortunate Dick was struck on the head by a cudgel and fell to the ground dazed. Initially, the excise officers were able to push the smugglers across the road but, as the fight developed, they were forced to retreat back to the Sheepmount side.

At one point, another of the excise officers William McDowall, was struck on the head by a cudgel and fell to the ground. Although he suffered a serious cut, he was wearing both a hat and a nightcap, this improvised protection saving him from ore serious injury or death. Suddenly, a shot rang out and one of the smugglers, Malcolm McGregor, shouted out to McFarlane, who was near him ‘Duncan! I’m gone!’ Unlike the other smugglers, McGregor was a labourer from Anderston but may have had relations in the Aberfoyle area. He had been struck in the left thigh and McFarlane pulled him over the wall bordering the road and into the trees, to conceal the wounded man from their opponents. Another of the smugglers, Peter McAlpine, had been knocked into the roadside ditch during the initial scuffle and, as he lay there, the excise officers rallied once more, forcing the remaining smugglers to flee back towards Maryhill.

Other than the officers mentioned, Nathaniel Ingram, Campbell Gardner and Neil Buchanan had also received injuries during the fight, but none was serious. Although they had driven off the smugglers, past experience suggested they might return with reinforcements, so the priority was to confiscate the whisky. By the time the officers began to gather the flasks, McFarlane and McAlpine had emerged from hiding and managed to recover two of them before following their companions away from the scene. Thus six flasks were picked up by the excise officers, who returned to Port Dundas once more along the canal towpath. As they did so it was established that three shots had been fired, one each from McDowall, Hugh Chalmers and William Kelly, although none could confirm having hit anyone. As the smugglers gathered together once more, they discovered that William McFarlane and Duncan Graham had been wounded, while Graham’s brother George and McGregor were missing. Both men were found lying behind the wall where Duncan McFarlane had left McGregor. The former was able to walk but it was obvious Graham was seriously wounded. A contact named Ferguson lived nearby, so they obtained a large sheet from him and used it to carry Graham back to the house, where it became obvious that both he and William McFarlane required medical assistance. Around 6am that morning, several of the smugglers appeared at the Royal Infirmary, where the wounded men were examined by two surgeons, George McLeod and James Watson. Graham had died by this time, while McFarlane was in poor condition, having his left arm and leg amputated. McGregor was examined by a third surgeon, William Penman, who removed a pistol ball from his thigh.

Although the Glasgow Herald had reported the matter was under investigation, it is probable most considered there would be no further action. Therefore it was surprising to find Chalmers, Ingram, Gardner, McDowall and Kelly all standing in the dock at the High Court in Edinburgh on Monday 14th June. While in hospital, Duncan Graham and William McFarlane had made two ‘dying declarations,’ although subsequently they did recover. Both remained in hospital by the time that the trial began and the Solicitor General, Henry Home Drummond, who was leading the prosecution, intimated that he would not use the declarations as evidence. However, knowing the smugglers remained in capacitated, one of the defence advocates, John Clerk, insisted they should be included, as they contained admissions that the smugglers had started the fight. Thinking that the two men would be unable to attend for some time and it was probable they would retract their statements in the interim, Clerk declined Drummond’s offer to have the trial delayed. Unfortunately for Clerk, the trial judge, Lord Boyle, the Lord Justice Clerk, had learned the men would be fit within a few days, so refused to allow the declarations to be included as he understood the men would be able to testify in person.

Dick was the first witness, stating that one of the smugglers had laid down his flask slowly when challenged but, as he moved forward to retrieve it, he was struck by the cudgel and stunned. He had been armed with a stuff stick but claimed he had not drawn it and used it only to fend off further blows. As he recovered, he had become engaged with another smuggler and, as they struggled, saw McDowall pull back from the man he was attacking and fire his pistol. At this point, Dick felt McDowall was having the worst of the struggle but, following the shot, he saw the smuggler run off. Another of the excise officers, Alexander Mudie confirmed that the smuggler he had tackled had laid down his flask and initially stood quietly. Then, as Dick was struck, the man took the opportunity to flee and, according to the excise officer he was not involved further in the fight, although his colleagues were hard pressed at one point. Another excise officer, Buchanan, confirmed that all but Ingram had been armed with stuff sticks, referring to the Bishopbriggs incident among others where it was known smuggling gangs had been armed and prepared to resist.

Although the declarations admitted the men had been involved in smuggling, none of them had been charged with any offence following this incident. Five of them gave evidence, Duncan McFarlane, McAlpine, McGregor, Samuel Cameron and Robert McLaren. All of them told identical stories, claiming that they had laid down the flasks when demanded and, although armed, used the cudgels only to fend off the blows of the aggressive excise officers. As each of the smugglers repeated the same story they drew a sarcastic comment from the Judge. He could not consider it true that ‘eight Scotchmen (sic) with sticks in their hands, would remain for five or ten minutes to being cut and slashed at, without ever striking a blow.’ When McLaren was asked whether the excise men could have seized the whisky without being armed, the Solicitor General tried to object to the question. However the judge over-ruled him and the witness was forced to admit they could not.

After hearing evidence from the surgeons who treated the victims, plus depositions by the accused, the court rose for the day. The jury contemplated their verdict all of the following morning before declaring the case against the excise officers ‘Not Proven’ at 1pm. Later it was learned that this verdict had been reached only by one vote, seven of the jury considering them guilty of culpable homicide. Before releasing them, Lord Boyle told the officers he considered the verdict correct but he had some comments to make. They were fortunate to have escaped punishment, both for failing to identify themselves and from refraining to use minimal force. Therefore, he warned them to be more prudent in future when faced with similar situations.

Although there were no further incidents recorded in the Maryhill area, the whisky smuggling trade continued to prosper until 1822, when greater powers were given to excise officers, followed in the next year by the Excise Act, which revolutionised the trade. Due to this the bottom fell out of the smuggling trade and the introduction of the legitimate whisky industry that exists in Scotland today. There is no record of when the cairn was erected at the side of Maryhill Rd, or by whom, although probably it was a spontaneous gesture by supporters of the smugglers. In the same manner that people with little or no connection see the need to leave flowers etc. at the site of modern tragedies, it is probable that local people and travellers from the Aberfoyle area had similar motivation.

While throughout the 19th century most Maryhill people knew about the smuggler’s stone, it appears that the details of the story were lost quite quickly and imagination allowed to roam freely. In consequence the following poem was published, probably around 1905, although the publication is unknown, having been discovered in a scrapbook in the Mitchell Library :

The Ghost of Kelvinside

There’s many a story you’ve heard me tell

How this and that and the other befell

But never, I’ve told of the awful ride Of the terrible ghost of Kelvinside

It was late at night as slone I sat

In my room in a cosy first floor flat

While I puffed my pipe the fire burned low

With hollows of crimson and purple glow

All was silent, and never a light

From the neighbouring windows around shone bright

Save the street lamp’s glimmer, which showed the way

Shining and wet ‘neath its flickering ray

For a storm of sleet, like a spectre bride

Whirled round my dwelling in Kelvinside

At two o’ clock, neither less nor more#

Came a muffled knock on my outer door

Who could it be at the hour of two

None could I think of, no one I knew

Would call me up at an hour so late

Unless his trouble and need were great

But I went and listened, then open’d wide The door to the Ghost of Kelvinside

My nerves were alert, my arm was strong

And I thought to myself “My friend you’re wrong if you think you’ll stagger a man like me”

So silent I waited that I might see

How the visitor, tall and weird, would deal

With a fellow whose nerves were “true as steel”

But the visitor bore himself with pride

And entered my house in Kelvinside

“Stop! Stop!” I exclaimed and upraised my hand But the figure advanced and would not stand

I barr’d his coming, but through my arm

He strode in a way that caused alarm

Limp, to my side, fell the outstretched limb

And the sight of my eyes grew dazed and dim

The fall of his feet never rais’d a sound

As he flitted from room to room around

Appalled I followed, and cold dead air

Was wafted about me as here and there

He paused, in apparent fruitless quest

In ancient habiliments quaintly derest

He knelt near a closet with ear to floor

And, I thought I detected a distant roar

Of voices like troopers in hot pursuit

Of a fugitive flying. The Ghost knelt mute

But over his visage a dark scowl came

And his sunken eyeballs seem’d darting flame

Then he rush’d to and open’d a window wide

And leapt to the roadway in Kelvinside

A phantom charger, awaiting him, paw’d

The gravel outspread o’er the roadway broad

But never a sound from the stamp of hoof

Caus’d echo from window, or wall, or roof

The champing of bit and rattle of chin

Should have sounded clear thro’ the driving rain

But naught was heard, tho’ a neigh seem’d to come

From the throat of the steed – but the steed was dumb

A vault to the back of the prancing steed

And off went the rider at lightning speed

But never the clatter of hoof on stone

Gave an indication of flesh and bone

A tremulous trail of a glimmering blue

Was left by the rider as on he flew

At times they leapt, as if obstacle lay

At places where nothing now bars the way

Then a shot rang out, and the rider and horse Fell prone to the earth – the rider a corse

I crept to my couch and hoped I might sleep I long’d for oblivion, clam and deep

With head under blankets, I strove in vain

To banish the spectre and slumber again

At length, with the dawn of daylight, I slept

Exhausted, and slumber my tired eyes kept

Haggard, unshaven, and bloodshot of eye

Was my morning look, and I don’t deny

I was rallied and “chaffed” by friends, in joke

On my way to the town, but no word I spoke

To al old time servant at once I went

And asked her to tell what the phantom meant

She told me the story, she’d heard when young Of a smuggler bold – who expir’d unhung – Shot where the passage from Forth to the Clyde

Winds near the old Sheepmount on Kelvinside

By the Aberfoyle clachan, from north he hied

With spirits for skippers who sailed from the Clyde

This story I’d heard from her as a child Just clear of the manor of Kelvinside

And I know that his ghost still fitful frets

O’er scenes of his sins (which it ne’er forgets)

For never a prayer o’er his shallow grave

Was uttered to hope his spirit to save

You will find old people in Maryhill

Remember the smuggler story still

But only a few of the oldest tell

The legend my nurse remembers well

“Go visit his grave,” she said to me

“and say the word’sleep’ – say it three times three”

So I did as bidden, beneath a shed

Which covers the spot where the man fell dead

And I hope that when next abroad he may ride

He won’t “call” at my dwelling in Kelvinside

-MONK BRETTON-

The author of this essay is a retired training manager who carries out research into less well known areas of local history in Glasgow and the West of Scotland. As a Maryhill native he has a particular interest in the history of the area and, especially, that of the old police burgh up until 1891. These essays are taken from the research notes that have been drawn up over a period of years and are intended as an introduction which can be used by those seeking more information.

Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust want to thank William Black for his incredible support throughout the years, having shared all his in-depth research and snippets since the start of the Trust’s journey into the history of the Burgh. We are also very grateful for allowing us to post his wonderful essays to our blog.

‘Hi there. Can I help you?’

Words by a volunteer

These are often the first words uttered by a volunteer when someone passes through the main doors of Maryhill Burgh Halls and until you get an answer, you have no idea what they’re looking for.

It could be someone looking for the offices of one of the tenants without realising that there’s a buzzer system and it’s your job to go outside with them and select the right buzzer; OR

It could be someone looking to view the latest exhibition – be it the gallus Glasgow suffragette Jessie Stephen or photos of Maryhill from fifty years ago – and it’s up to you to show them where the exhibition is, point out a couple of things and then stand back and let them do the talking. It’s amazing what you’ll learn; OR

It could be a wee girl in for the regular music lessons with her granddad and he’s given her some money to spend in the well stocked shop - buttons and bows can be a girl’s best friend; OR

It could be someone who’s not been in the Halls for many years – or maybe never at all – who are amazed at how the modern offices and recording studios exist in tune with the refurbished main hall with all the fantastic stained glass from about one hundred and fifty years ago and the other, slightly more modern, stained glass from when the Halls were saved from destruction about twenty-five years ago. There’s that tremendous WOW factor when you walk through the doors from the modern to Maryhill’s past history – all in stained glass, waiting to be admired; OR

It could be the recognition of the amazing talent of Jo Sunshine and her story, as they walk past her crayon and pastel works encompassing so much of the world, including unicorns and Lock 27; OR

It could be how the Heritage Wall outlining the path of the Forth and Clyde Canal through Maryhill is complemented by the replicas of all the stained glass which show the many trades that grew up beside the canal; OR

It could be the surprise of a young person when you take them up the stairs to the mezzanine floor and explain what the clippie would do with all the seats upstairs on a tram when it reached the terminus but didn’t need to turn round before it started its return journey. Older folk just make a sweeping gesture with their hands, cos they know, and they recognise the signage from the Olde Tramcar Vaults pub; OR

It could be smiling at all the youngsters coming and going from the Primrose Nursery and whilst it’s not compulsory to say ‘Hi’ to the children, we all do; OR

It could be pointing out the Firemen Gates, as they leave the Burgh Halls with a smile on their faces, and explain that they were made by Andy Scott of the Kelpies’ fame and reflect the time when the building played host to the Fire Station, the Police Station and the local steamie; OR…….

Well, whatever it is, as a volunteer, hopefully you’ve answered their questions and they go away to tell their friends about the friendly reception that they got from the folk at the friendly reception where they bought some smashing Maryhill Burgh Halls souvenirs but the real attraction is Maryhill Burgh Halls. It’s the building that’s the star.

Revisiting The Maryhill Corridor - What Happened To It

Words by John Thomson

Maryhill Road, late 1970s [Photograph by George Ward]

It literally fell on my lap as soon as I opened the book – obviously a book I’d not looked at for some time as ‘it’ was a newspaper cutting from the Glasgow Herald of 8th May 1980 and it told of the good times coming to Maryhill. It was written by Murray Ritchie, who held many editorial posts with the Herald and was a superb wordsmith.

He spoke of an imaginary someone, just before or after the war, taking a red tram down Maryhill Road towards Glasgow city centre; ‘It (the tram) would have been packed and noisy – almost as noisy as the streets where women crowded the hundreds of small shops and children filled the pavements. It was a teeming, sometimes tough, self-reliant district in a successful city. It was a community.’

But he then spoke of a major change in the view from the top deck; ‘Today (1980) the blue bus sweeps commuters in from Bearsden and Milngavie past dereliction and desolation. The lifeblood of Maryhill dried up years ago leaving crumbling tenements and acres of rubble and red blaes.’

So, what had happened?

Well, like much of Glasgow there was to be a motorway, scything through Maryhill to allow those commuters to take their cars to work in Glasgow and back home to the commuter belt, but unlike much of Glasgow, eventually, there was no motorway. It would have used the, then, almost derelict Forth and Clyde Canal towards Gilschochill and gone through what is now the well established area of Summerston, which, itself, continues to expand.

It just never happened. Many Maryhill residents were against it and made their feelings well known to the city planners. The planners did take some notice and various modifications were suggested but changing politics and politicians saw its death knell. In 1975, the creation of Strathclyde Regional Council and new district councils led to a re-evaluation of the roads programme and the Maryhill Motorway was dropped. However, as James Craigen, one-time MP for Maryhill put it,

‘By the mid-1970s, Maryhill Road was in a sorry state and planning blight had put an official stamp on deterioration.’ Many local businesses had closed and a lot of the tenements had been demolished – some of this as preparation for the motorway. Gap sites and large areas of vacant land proliferated. But help was at hand.’

In 1977, various organisations, including the Scottish Office, Glasgow District Council, Strathclyde Regional Council and various public agencies such as the Scottish Special Housing Association got together and announced the arrival of the Maryhill Corridor Project complete with a Corridor Working Party the next year. It was launched to ‘tackle the urban plight and improve the wider area – of which the spine was Maryhill Road’ and to lead ‘a co-ordinated attack on deprivation in Maryhill.’

Certainly there were many local authority planning officers involved and various advice centres were established to encourage Corridor consultation.

It promised much, and did deliver some of that. There was new housing in the area and new industrial development and much of that remains with us today. The Maryhill Shopping Centre was opened in 1981 at a cost of £7.5 million on the site of the former Maryhill Central Station and, just a wee bit further up Maryhill Road, the modern world was welcomed with the establishment of the West of Scotland Science Park, opened in 1983 by Princess Anne. Indeed, much of the more modern stained glass in the Main Hall at the Burgh Halls reflects many of these developments.

On a more mundane level but to some, equally as important, four new public conveniences were to be built at Summerston, Maryhill Central, Queen’s Cross and St George’s Cross but these never happened.

And on a cultural level, the West End Times of 18th June 1982 outlined all the events that were to take place the following week in the Maryhill Corridor Festival (1982). Among the many events were the Festival Queen Competition, a Grand Gala Procession, and an ethnic dance and photographic exhibition, as well as range of arts and crafts workshops, folk concerts and theatrical performances. However, infuriatingly, there is no reporting of any of these events in subsequent editions of the West End Times. Did any of it happen? It was, after all, only forty years ago and it may be that you, the reader, remember these events or even took part in them.

The Maryhill Corridor Project came to an end in 1984 ‘against the pressure on resources and claims from other parts of Glasgow.’ (Jim Craigen) but there had been high hopes for it. Indeed, it has been claimed that much of that pressure came from the need to make sure that Summerston had none of the failings of earlier peripheral estates in Glasgow, including community facilities. Murray Ritchie, whose words opened this research, echoed those hopes with his final words;

‘When the Corridor plan was announced it was described as the “kiss-of-life” which would transform Maryhill into a “garden suburb” and restore it to its former place in the heart of Glasgow as “one of the most lovable parts of our great city’’.’

Do you have memories of the Maryhill Corridor Plan – its hopes and aspirations – and what its legacy is? It was only forty or so years ago. We would be keen to know. Indeed, you may even have been the Corridor Festival Queen of 1982. Or could any of the plans be used today to improve the area? Is the idea of a garden suburb still a reality? Please let us know.

You can either comment here or, for longer thoughts, please email info@mbht.org.uk

—

Credits for much of the information in this article must go to Murray Ritchie (‘A glimmer of hope at the end of Maryhill Corridor’ Glasgow Herald, Thursday 8th May 1980), James Craigen (‘Memoir on the Road through Maryhill’, September 2003) and the staff at the very helpful Special Collections of the Mitchell Library.

Clock In The Lum

Words by William B. Black

The old burgh building at the corner with Fingal Street. Maryhill Cross can be seen in the background. Picture from Guthrie, H. Bygone Maryhill (Stenlake Publishing: 2007)

The clock in the lum was a Maryhill legend in its time as well as being a central feature of the original burgh buildings.

When Maryhill became a police burgh in 1854 it required a building that combined council chamber and offices, court and police station. To meet this a former bakery which was sited almost opposite the White House and at the corner of the Modern Maryhill Road and Fingal Street was converted for the purpose.

At that time many members of the public relied on clocks on public buildings to provide them with information about the time. In addition, although of modest dimensions, some of the new commissioners considered that a clock was required to enhance the status of the building. They, along with other local business men, came together to finance this and, in November 1857, the clock was unveiled.

To make the right impression it required to be in a high part of the building and, ideally, a new clock tower would have been the best solution. Instead, it was decided to place the clock at the base of the chimney stack that was position centrally on the front elevation of the chambers. This proved problematical, as its close proximity to the flues subjected it to variations in heat, along with exposure to soot ingress. It appears also that it was not fitted with a protective glass cover over the dial, giving a further problem of water damage. This would be exacerbated by its exposed position, facing westwards across the Kelvin valley.

March 1863 saw the wedding of Edward, Prince of Wales, to Princess Alaxandra, an event that was celebrated with a grand ball in the burgh chambers. It was alleged that, during this, one over-exuberant guest started ringing the bell attached to the clock, resulting in its later notoriety over accurate time-keeping.

Eight years later, Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, was due to marry the Marquis of Lorne, and this prompted a poem from “A Canny Scot” in the Dumbarton Herald of 16th March 1871, entitled The Maryhill Police Clock. This warned against any repetition of the high jinks of 1863.

In wha’s bunnet is a bee,

When the Prince o’ Wales was married

He set me a’ agee.

Ding! Dong! Ding!

He pu’d the string’

And many rugged he;

He shook me a’

Big wheels and a’

And now I’m what you see.

And as Louise is getting wed,

The body may gang wild;

And bring us baith doon o’er his head,

wi’ sic a din and thud

A stitch in time

Often saves nine

Forewarned’s forearmed they tell;

So if ye be

In merry key

Tug canny at the bell.

In 1874 apparently there were further complaints about the clock, voiced in correspondence in the Dumbarton Herald. On 11th April 1872 a further poem appeared in the newspaper, this time allegedly a plea from the clock itself to the police superintendent, Captain George Anderson. It was titled An Epistle from the Hall Clock to Captain Anderson.

Dear Geordie, gin I had my wull,

O’ that officious body near the Bull,[i]

I’d bring my pendulum o’er his skull

Wi’ sic a crack

I’ll gie him yet his bellyful

Or break his back

Se what he did in papers say,

To think o’t yet my heart is wae;

Last Thursday being the Fast Day,[ii]

Great crowds did come

To see the boats sail up the brae[iii]

And me I’ the lum

The louns aroun’ did gibe and gaffe;

Baith the weel-to-do and the riff-raff.

Like to a time when auld Calcraf [iv]

is brocht away

Frae hame, to polish criminal aff,

‘cording to law.

Daft D____ was among the crowd,

Tho’ his talk’s not easy understood;

He aye look’d up and said fu’ proud,

Wi’ rougish glee –

“Somebody says” he spak out loud

“it is daft like me.”

At ilka curious upturned face

As weel’s I could I made grimace;

And as soon’s you like get a glass case

To keep me richt;

And a bleeze o’ gas to let a’ the place,

see the hours at night.

The man wha heard me chap thirteen,

just said it in a fit o’ spleen;

Though I doubtna’ but sic things hae been

The proverb says;

“corbies shouldna’ pick out corbies’ e’en”

let him mend his ways

The pleasures seekers used to run,

by the Three Tree Well, and Kelvingrove;[v]

and seek the hermit, fancied cove.

That hallowed spot

Thae wonders noo I’m classed above

By the Canny Scot.

Great things spring whiles frae but sma’ germs,

And I hear you’re on the closest terms,[vi]

Wi’ the Lord Lyon, King at Arm,

Wha’s comin doon

To sketch me in a coat of arms[vii]

For our auld toon.

Now dinna’ think that I’m uncivil,

For sending to the printer’s devil,

To set and press this rhyming drivel;

Sae I’ll quat my pen;

May the Lord preserve you from a’ evil.

Amen! Amen!

The Police Clock

The Lum April 8th 1872

By September 1877, with the new burgh buildings nearing completion, consideration was given to the future of its predecessor. It still remained an inaccurate time-keeper and, when it was noted it was striking One o’ clock when it should have been denoting six, another brief poem appeared in the press.

Whiles it wags awa’

but it’s oftener standin’ still

It’s as gude’s nae clock ava’

The clock at Maryhill[viii]

Despite this it retained its loyal fans and, on Hogmanay 1877 a group of young men gathered to greet the New Year for one final time at the old building. They positioned themselves at the stone magazine on the opposite side of Maryhill Road, or Main Street, as it was known then. This magazine survives today, being the inshot in the canal boundary wall just north of the White House. The clock in the newly constructed barracks was heard to strike midnight, along with the sound of the pipes and rums, greeting in 1878. This was followed almost immediately by the bell at the newly opened Gas Works at the foot of Butny Brae. Still the clock in the lum maintained a dignified silence and, after a further few minutes, deigned to acknowledge the sizeable crowd of supporters standing opposite. As the clock began striking the assembled throng cheered lustily then, as the last notes died away across the valley, dispersed to continue their revelries elsewhere.

Consideration turned towards the future use of the old building, a proposal to convert it into a Working Men’s Mechanical Institution receiving a poor response locally. An advert was placed in the Glasgow Herald on 20th January 1878 but apparently did not produce any decent offers. The old clock was allowed to run down, leading in January 1879 to numerous complaints to the commissioners. Probably reluctantly, they had it serviced and in operation again by May, although it continued to be reported as producing and “uncertain sound,” while maintaining its reputation for poor time keeping.

June 1880 saw the commissioners decide to expose the buildings for rental and, in September, they received a conditional offer. This came from Thomas Reid, a Glasgow tobacconist, who was to become the owner of several public houses within the city in the last decades of the 19th century. He offered a price of £1800 subject to his being granted a hotel and inn licence, good title, free of all bonds (loans) and entry by Martinmas (December 1880.) One of the commissioners, the architect Alexander Petrie, pointed out that the Union Bank held security on the buildings, negating one of Reid’s conditions while it remained. The bank had made inquiries when it was forts placed on the market and Petrie suggested that they be approached once more. Probably aware that Maryhill had ample public house provision, Petrie suggested that the bank would be a superior owner. Unfortunately, by this time the bank had premises in a handsome building that survives today at 1944 Maryhill Road.

By October it had been learned that Reid’s application had lapsed and the future of the buildings and the clock were in doubt once more. By this time the clock was out of order once more, despite having been overhauled in August and a Mr Desh being tasked to keep it wound properly.

The continued complaints about the clock led to the publishing of a last poem in the Dumbarton Herald of 23rd October 1880. Patrick Carrigan was an Irish born nail maker, who had lived and worked in Maryhill since the 1840s and who had died recently. It is probable that as well as a reference to the clock, it is a farewell to a well-loved local worthy.

PAT CARRIGAN’S DEFENCE OF THE CLOCK

He’d put a certain gooson from the makin’ o’ songs,

If he had his nose in his ould smiddy tools;

Aya and red hot we’d mak’ them, at least so he says

With his brogue, his blarney and bletherin’ ways

The clock he declares to be good of its kind

Tho’ it’s sometimes too fast, or a little behind.

For all of us vary betimes, so he says

With his brogue, his blarney and bletherin’ ways

The man at the lock is a dirty spalpeen

For sayin’ he heard it strikin’ thirteen;

I will show that it never could do it, because

With my brogue, my blarney and bletherin’ ways

Once more the old building was advertised, this time to be rented out rather than sold, one suggestion being that it be converted into a model lodging house. Although its ‘fan club’ appears to have disappeared, at least one member remained faithful. On Hogmanay 1880 a drunk was found, sitting on the magazine wall, “waitin’ for the clock tae bring in the New year.”

In February 1881 it was revealed that Dr William MacDonald had agreed to convert the old burgh buildings into a surgery, while extending the living accommodation for use by his family. This was ironic, as Dr MacDonald was a strong critic of the commissioners and would be one of those who campaigned for amalgamation with Glasgow, which occurred in 1891. He died in 1897 but the buildings continued to be used as a surgery until 1948, when it was demolished. The clock continued to be maintained, this being taken over by Glasgow Corporation by the end of the 19th century but kept its hard won reputation for its singular method of telling time.

Today the site is occupied by a small tenement block, next to Kilmun Street, originally built in the 1950s as police housing.

NOTES

[i] The “Bull” referred to is the Black Bull Inn, which lay to the south of the burgh hall and was one of the early hostelries in the village. Unlike many of the others it appears to have been of good reputation, supervised for many years by Mrs Martin, then her daughter Isabella. At the founding of the burgh, it housed the commissioners’ meetings until the burgh court was ready, then was the scene of many burgh functions until the building at Gairbraid Avenue was completed in 1874

[ii] In the 19th century the Church of Scotland still held regular fast days, in which members were expected to practice abstinence in all things. By the 1870s they had become holidays for many working people, who would take the opportunity to enjoy a day out of the city where possible.

[iii] Opposite the burgh hall was the start of the flight of five locks which led down to the Kelvin Viaduct on the Forth & Clyde Canal (Locks 21 to 25) In an area when there was regular traffic through the canal in both directions, this would be a place of great activity and a great attraction to the population. As an added attraction, in the adjacent Kelvin Dock was the shipyard of J & R Swan, birthplace of the Clyde “puffer” and there would be several vessels under construction to be inspected, if only at long range.

[iv] Calcraf was the public executioner

[v] This is a reference both to a local beauty spot and the famous song “Kelvingrove” written in 1821 by Thomas Lyle. The Three Tree Well (also known as the Pear Tree Well) lay close to the Kelvin near the present day Ford Road. It was a favourite trysting spot for young people, until one girl was found murdered there. The murder was never solved but the “traditional” story is that the culprit was a jilted lover. When the railway was built through Kirklee, the well was buried in the banking, although today water from it seeps intermittently down into the Kelvin. “Kelvingrove” was written in praise of the gorge which runs from Garrioch Quadrant down approximately to Queen Margaret Drive. Due to the name being used at a later date for a house further downstream, it has been incorrectly associated with the area in which the Art galleries stand.

[vi] Capt. Anderson was well known for “social climbing” in Maryhill

[vii] In the end the coat of arms was produced by Alexander Thomson, pattern designer at Maryhill Print Work and chronicler of the 19th century burgh, to whom all of us owe a great debt for the information he recorded. Although included in a later book by a Lord Lyon King at Arms, it appears that the arms were never registered (that cost money). This came to light In 1955, when North Kelvinside Senior Secondary School were seeking to use them as part of their revised school badge.

[viii] Lennox Herald, 27th January 1877

The author of this essay is a retired training manager who carries out research into less well known areas of local history in Glasgow and the West of Scotland. As a Maryhill native he has a particular interest in the history of the area and, especially, that of the old police burgh up until 1891. These essays are taken from the research notes that have been drawn up over a period of years and are intended as an introduction which can be used by those seeking more information.

Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust want to thank William Black for his incredible support throughout the years, having shared all his in-depth research and snippets since the start of the Trust’s journey into the history of the Burgh. We are also very grateful for allowing us to post his wonderful essays to our blog. This is the third one of the series, you can read the first one on shipbuilding by clicking here and the second one on the estate of Maryhill here.

The Estates that made Maryhill

Words by William B. Black

Map of Maryhill estates divided by the River Kelvin

Prior to the Reformation the area known today as Maryhill was the property of the Diocese of Glasgow, which stretched over a considerable part of south west Scotland at one point. In 1175, William the Lion declared that Glasgow was to be a Burgh of Barony, under the continued control of the Archbishop, Jocelyn.

This covered not only the town but an area roughly from the banks of the Kelvin in the west to Shettleston in the East and included Govan on the south bank of the Clyde. Following the flight of Archbishop James Beaton in 1560, the area came under the control of the Protestant church and, in 1611, the town of Glasgow was promoted to the status of a Royal Burgh by James VI, but the area around it continued as a barony.

Even before the Reformation, the area had been divided up into estates and farms, whose occupants feud the land from the Church. When this control loosened in the late 16th century, others moved in to take over control, including Walter Stewart, Commendator of Blantyre. A commendator is defined as someone having a temporary holding of an ecclesiastical benefice but Walter’s holding proved permanent. In 1587 James VI transferred the Barony charter to him and on the list of estates contained within are Garroch, Gairbraid and Rouchhill, one of the earliest references to areas that remain part of Maryhill today.

At the time that the early village developed, the core of the district was considered to be Gairbraid and we know that it existed as early as November 1515, when Alan Duncan feued part of it. More significantly in 1536 John Hutcheson inherited another part following the death of his father. Gradually over the next decades the family obtained larger parts of the estate and in August 1600 it passed to George, who was a great-great nephew of John. George’s father, Thomas had inherited the adjacent estate of Lambhill, which had passed to his other son, also Thomas. Today George & Thomas Hutcheson are remembered through Hutchesons’ Grammar School, and the building known as Hutchesons’ Hospital in Ingram St.

Gairbraid House by David Small (Glasgow Life)

The Hutcheson brothers were solicitors in Glasgow and appear to have been very adroit at adding to their property portfolio in the early years of the 17th century, often from deceased clients. George died in 1639 and Thomas three years later, both without any children and their estates passed to their three sisters. One of them had married Ninian Hill in 1609, who died around 1621 but he brought with him the small estate of Garroch, now referred to as Garrioch. Helen had a son also called Ninian and she passed on the inheritance of both Gairbraid and Garrioch to him soon after the Hutcheson brothers died. Her sisters did likewise and Ninian gained Lambhill, giving him an estate stretching from the banks of the Kelvin to Balgrayhill in Springburn.

Gairbraid and Garrioch were passed down through successive male generations of Hill, until 1738 when it was inherited by eight year old Mary, who lived in Greenock. Around 1761, Mary married Robert Graham, a former merchant navy captain, whose father had purchased Lambhill in 1700. By this time the Glasgow area was beginning to develop commercially, but Gairbraid was encumbered by debt and unable to provide much capital.

To ease the burden, the Grahams sold land on which he had attempted to mine coal without much success to Sir Ilay Campbell, owner of Garscube estate, in return for an annuity. Then, in 1785, it was announced that the Forth & Clyde Canal was to be extended westwards from its terminus at Stockingfield on the adjacent Ruchill estate.

To do so, land was purchased from the Grahams and, with their finances more secure, they decided that they must have a more fashionable house in which to live. The original Gairbraid House had been built in 1688, but in 1789 they had a new Georgian mansion constructed overlooking the Kelvin, with a tree lined drive from the Drymen Toll Road, this surviving today as Gairbraid Avenue.

The toll road, known as Garscube Toll, had been constructed in 1753, another windfall for Gairbraid Estate, although it divided their land rather awkwardly. Then, when the canal was being built, it was realised that the road would require to be moved to enable an aqueduct to be built across it. At this time it ran behind the site occupied today by the library and a 90o turn was built just below the line of the canal taking it down to the modern Maryhill Road. Beyond this, a new length of road was built running to the top of the hill, rejoining the original where it turns at Kelvin Dock. This left a cul de sac, running from the north bank of the canal to the toll road, known today as Aray St., with a narrow strip of land between the two. This would prove unsuitable for agriculture but the canal brought the potential of further industrial development. Therefore in 1787, the Grahams advertised it as a series of building plots and Robert saw an opportunity to enshrine his wife’s name in the area for future generations. At this time, it was fashionable for new areas being feued off to be named either with the family name of the seller or, possibly romantically with that of the lady of the family. It was the initial feus of these properties that contained the term ‘in the village known as Maryhill’ but, it took several decades for the name to become established.

By 1809, both Robert and Mary were dead, leaving two daughters, Lilias, who never married and remained in residence at Gairbraid until her death and Janet, who married Alexander Dunlop of Greenock. The estate passed to their son John but after Lilias’ death occupancy passed to a series of tenants. By 1923, it had been divided into flats and it was demolished a few years later.

Garrioch House

Closely connected to Gairbraid is the estate of Garrioch, which appears for the first time in 1512 and passed through several hands before coming into that of Marion Wilson, who married James Hill of Ibrox in 1582.

As seen above, their son Ninian married Helen Hutcheson in 1609. At this time it appears that Hill did not inherit the whole estate as, in 1597 half of it had been feued by Blantyre to John Wylie, Clerk to the King’s Chancel.

When their son Ninian inherited it appears to have been quite extensive, a 1680 description suggesting it ran from the modern Queen Margaret Bridge along the Kelvin to Kelvindale Rd, then followed this along a line that eventually met the Western Necropolis, then ran diagonally across St Kentigern’s Cemetery to its SW corner. From there, the boundary ran back to the point where the railway line crosses the canal, then goes back down it to Stockingfield. It then runs along the Glasgow Branch to Bilsland Dr, before heading back down to its starting point at Queen Margaret Bridge.

By the time Glasgow merchant William James Davidson bought it in 1827, it had shrunk and, when the War Office were looking for a site for new barracks in 1872, the bulk of the estate was sold off for this purpose. Of course, once the barracks closed in 1958 the logical move would have been to bring back the original name for the new housing estate but, instead, it was given that of Wyndford, originally a small area adjacent to the canal at Lochburn Rd.

Ruchill House by David Small (Glasgow Life)

The estate that appears to have gained most from the breaking up of Garrioch was Ruchill, once the largest within the Maryhill area. Like the others, it appears initially in the surviving records at the beginning of the 16th century, when it was owned by Edward Marshall. It followed the usual pattern of being inherited by several generations, at least two through the female line, but by 1658 it was in the hands of a Glasgow merchant, Thomas Peadie. He was one of the proprietors of the Eastern Sugar House in Glasgow and at one point was provost of Glasgow, the first Maryhill resident to do so. He appears to have been a ruthless individual, who died in 1717, passing the estate to his son James, the second person from Maryhill to become provost of Glasgow.

Peadie died in 1728 but his son John was the last male heir, his two sons both dying before their father. This resulted in the estate being divided between his five aunts. At this time, it stretched from just east of the former Ruchill Hospital all the way down to Great Western Rd, including Kirklee and a large portion of Kelvinside. Given their pedigree, it should not be unexpected that they could not agree on the division of the estate, including their home, Ruchill House. It had been built around 1700 and was a simple house, located approximately at the north end of the modern Whitworth Gardens. Like Gairbraid, access was along a drive from the parish road, which ran close to the Kelvin, this surviving today in the form of Shakespeare St and Ruchill St.

Robert Dreghorn

During the dispute, a surveyor had been brought in to value the estate and, once the matter was settled, he made an offer to purchase it. All but one sister, Grizell, agreed and the bulk of it passed to Alan Dreghorn. He was part of the Glasgow elite but is remembered today for his design of the magnificent St Andrew’s Church south of Glasgow Cross. He died childless in 1764 and the estate passed to his nephew Robert, better known to his contemporaries as ’Bob Dragon.’ As a child, he had suffered from smallpox, which left him with a badly disfigured face, although to compensate he became one of the best dressed men in Glasgow. While considered eccentric, he was a man who was well aware of the value of his property and also ensured that he was never undersold. This tendency contributed to delays in completion of the Forth & Clyde Canal to Stockingfield, as it went through his estate and Dreghorn held out for the best price available.

Dreghorn committed suicide in 1804, the estate passing to his sister Elizabeth, who also died childless in 1821. This resulted in the estate being inherited by her niece, Isabella Dennistoun, who placed it up for sale in 1826. The buyer was William James Davidson, another Glasgow merchant, but by 1860 Ruchill House was being advertised for a furnished let. In 1875, it became the club house of the Glasgow North Western Golf Club, who laid out their course to the north and west, part of it surviving today close to the canal. At the beginning of the 20th century, much of the estate came under the ownership of Glasgow Corporation, with Ruchill Hospital and Park being built on the southern half. The house was demolished in 1927 and much of the area built over for council housing.

Kelvinside House by David Small. This view drawn from the north west includes in the foreground the land occupied formerly By North Kelvinside School playing fields and Kelbourne School (Glasgow Life)

The portion of Ruchill that had been retained by Grizell Peadie lay to the south east and straddled the Kelvin. It became known as Bankhead until she sold it to Thomas Dunmore, a Glasgow merchant in 1749. Immediatel,y he renamed it Kelvinside and, in the following year, he had a magnificent mansion built, its position being approximately at the top of the hill in Clouston Street, on its north side. The western half of the latter formed the main drive, which ran down to the parish road along the Kelvin.

Dunmore’s son was one of those who suffered financially during the American Revolution and, in 1785, it was sold to Dr Thomas Lithian of the East India Company. After Lithian died, his wife Elizabeth remarried, her second husband being Archibald Cuthill, a Glasgow solicitor. It was during their ownership that Kelvinside House saw the birth of Henry Campbell-Bannerman in 1836, the only person born in Maryhill to become UK prime minister, at least to date.

Matthew Montgomerie and John Park Fleming purchased the estate from Cuthill’s widow in 1836 and they began to consider plans to develop housing upon it. The formation of the Burgh of Maryhill in 1856 effectively split the estate in two, with the Kelvin marking the internal boundary. In 1869, 93.4 acres of the Maryhill part were sold to John E Walker, who set about developing much of the area we know today as North Kelvin. Simultaneously Fleming’s descendants became responsible for developing the housing that was to form Kirklee and Kelvinside.

The remaining estates had small portions that were included within Maryhill, that immediately bordering Kelvinside being North Woodside, which had passed from the Church to Adam Colquhoun , Rector of Stobo. From there it went to his daughter, Elizabeth, who had married Sir George Elphinstone, provost of Glasgow.

Stevenson Memorial Church by Tom Maxwell

However, by the early 17th century it had passed into the hands of Colin Campbell and it remained with that family until 1694. Then it passed to Archibald Stirling of Kier and this heralded a period when it changed hands at regular intervals. By 1804, it was owned by Colin Gillespie, a Glasgow calico printer but, by 1822 he had gone out of business and the estate passed temporarily into the hands of the bank. They sold it on to an accountant John Paul, who retained ownership until 1845. After a short period under the control of John Bain, it became the property of the ill-fated City of Glasgow Bank. They began to develop the area for feuing and, to improve access to the city, built the handsome Belmont St Bridge.

To the north of the burgh two estates infringed, the larger being Garscube, which remains largely intact today. Originally owned by the Lennox family, in 1250 it had passed to the Colquhouns, who retained it until 1681 when it was purchased by John Campbell of Succoth. This family was to retain ownership until 1947 when it passed to the University of Glasgow. During the period of the burgh the Campbells of Succoth were seen as the local lairds, having Garscube as their principal residence.

Sir Ilay Campbell of Succoth (1734 - 1823) by David Martin

Probably the best known of the Campbells of Succoth was Sir Ilay, who rose to become Lord Advocate in 1790 and was one of the most influential men in Scotland at this time. During their occupancy, they provided support for several Maryhill institutions. Lady Elizabeth, wife of Ilay’s grandson Sir Archibald, provided small pensions for several impecunious local residents. The following Lady Campbell, wife of Sir George, went further by financing the building of a cottage hospital, a building that survives today at 2024 Maryhill Road.

Inevitably there came a point where the Campbells were no longer able to maintain their position at Garscube and, in 1947, it was sold off to the University of Glasgow, the Maryhill section today being occupied by the Science Park, where space satellites are designed for international customers.

The final estate is Killermont, the bulk of which forms the golf course, with its magnificent Georgian clubhouse. In the early 16th century it had belonged to Sir John Cunningham but, after several other owners, in 1747 it passed into the hands of Lawrence Colquhoun. This family remained in charge throughout the 19th and early 20th century, having changed their name to Campbell-Colquhoun when the estate descended through the female line. Although their contribution to Maryhill was less, they did finance the building of the second Parish School and a later extension, this being on the site of the present Maryhill Parish Church. Originally, all of the estate had been on the western side of the Kelvin but at one point the area known as Sandyflats on the Maryhill side was purchased from the Grahams of Gairbraid. Today a large part of this area is occupied by the Riding for the Disabled Equestrian Centre.

The author of this essay is a retired training manager who carries out research into less well known areas of local history in Glasgow and the West of Scotland. As a Maryhill native he has a particular interest in the history of the area and, especially, that of the old police burgh up until 1891. These essays are taken from the research notes that have been drawn up over a period of years and are intended as an introduction which can be used by those seeking more information.

Maryhill Burgh Halls Trust want to thank William Black for his incredible support throughout the years, having shared all his in-depth research and snippets since the start of the Trust’s journey into the history of the Burgh. We are also very grateful for allowing us to post his wonderful essays to our blog. This is the second one of the series, you can read the first one on shipbuilding by clicking here.

Shipbuilding in the Burgh of Maryhill

Words by William B. Black

‘The Boatbuilder’ by Adam & Small (1878), Glasgow Museums

Situated some distance from the Clyde Maryhill may appear an unlikely situation for a shipbuilding yard but, during the 19th century it produced a significant number of vessels, both coastal and deep sea.